All morning I had been staring up at the wide slot chimney that would be my first pitch of the day. As we started jugging the fixed lines, my heart pounded. All I could think about was the unknown. My palms began to sweat and mouth went dry. I tried to block it out and focused on the 9.2 mm cord my life was connected to. Step, slide the jumar up, step again, and repeat. Below me, Chris was jumarring up the fixed ropes like a machine.

We reached our high point on the route, a comfortable flat ledge that sat directly below the chimney pitch. I swallowed hard, trying not to let Chris know I wasn’t psyched about the ominous looking chimney.  Taking a deep breath, I remembered how much I loved the act of climbing and started upward before a loose flake on a small ledge brought me to me a full stop. I reached out to test it. The body sized flake see-sawed back and forth ready to drop into the void with the slightest touch. “Shit, Chris! This thing is ready to go…I can’t get past it”, I said with my stomach in my throat. I assessed the situation. If I released the flake all I could think is that it was going to take out Chris and the ropes. It was about this time I wondered why the hell I had ever wanted to do a first ascent.

Taking a deep breath, I remembered how much I loved the act of climbing and started upward before a loose flake on a small ledge brought me to me a full stop. I reached out to test it. The body sized flake see-sawed back and forth ready to drop into the void with the slightest touch. “Shit, Chris! This thing is ready to go…I can’t get past it”, I said with my stomach in my throat. I assessed the situation. If I released the flake all I could think is that it was going to take out Chris and the ropes. It was about this time I wondered why the hell I had ever wanted to do a first ascent.

Months earlier, I was sitting in my favorite coffee shop in Minneapolis on a cool spring morning. I was dreaming of alpine starts, the feel of granite under my fingertips, and long splitter hand cracks shooting skyward. I scrolled through my emails. The American Alpine Club had sent out an invitation to apply for the Live Your Dream (LYD) Grant. My mind raced with idea after idea. What was my dream? What did I aspire to do as a climber. Well, for one thing, I was in the midst of embarking on a pet project – to climb fifty inspiring ascents by the time I turned fifty. I had two years to complete this monster project, and the one thing that was missing from my climbing arsenal of big routes was establishing a first ascent.

I looked back on my progression as a climber. Following my mentors, I gravitated toward traditional climbing. I loved being off the ground with lots of exposure below my feet and the possibility of adventure. Trips took me further into the greater ranges where long, all day routes were what inspired me. Soon, I was drawn to the big walls of Yosemite. I wanted to hang off the side of the “Big Stone”, tethered to the rock and my partner with a higher level of commitment. On my ascent of The Nose on El Capitan, we were passed by a Nose in a Day (NIAD) team, and I saw the future. Multi-day routes in a day! Two years later, I completed Half Dome – in a day.

The next natural step was to establish a new line, from the ground up, for future generations of alpine climbers. My friend Chris Hirsch, a prolific young first ascensionist, had recently learned of a remote wall in the Cloud Peak Wilderness, in central Wyoming. I contacted Chris and told him about the LYD grant application.

The next natural step was to establish a new line, from the ground up, for future generations of alpine climbers. My friend Chris Hirsch, a prolific young first ascensionist, had recently learned of a remote wall in the Cloud Peak Wilderness, in central Wyoming. I contacted Chris and told him about the LYD grant application.

I explained to Chris that I wanted to establish a route in honor of Todd Skinner and Paul Piana, two well known climbers who had first located the wall while flying over the Cloud Peak some 20 years earlier. With Paul’s assistance, Chris had established a new route on the same formation the previous summer and identified several others that were ripe for the plucking.

For those who knew him, Todd was a modern day cowboy. He grew up in Lander, Wyoming, a little cow town that sits tightly against the front range of the Wind River mountains. His childhood and adolescence were a combination of mischief and adventure. His love for the mountains and connection to the outdoors rubbed off on anyone who knew him. He had an endless thirst for developing new routes, opening up new climbing areas, and sharing his treasures with the rest of the climbing community.

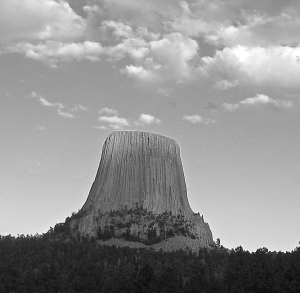

Growing up in the middle of the U.S., many of my climbing trips were to Wyoming where Todd had left his mark – Devil’s Tower, the Wind River Range, Wild Iris, Sinks Canyon, and the Grand Tetons. I would often find myself standing below a route that had been established by Todd or Paul in utter disbelief that it could be free climbed.

Todd died in 2006, as a result of a climbing accident in Yosemite National Park. He was 47 years old. Todd left behind his wife Amy Skinner and three young children. His family, partner Paul, and the entire climbing community were saddened by the tragedy surrounding his death.

I identified with Todd, his love for high places, and being a family man myself. Leaving my wife and son behind to climb a remote peak, without the certainty of pitch-by-pitch route descriptions that I had been accustomed to, left me on edge as we began to plan our route. But like Todd, the allure of the mountains called to me like a siren song.

Chris and I planned to meet up near his home in Rapid City, South Dakota, while I was on the tail end of a summer road trip with my wife and son. We would launch from the Black Hills, with my good friend and climbing partner Steve Wilger, who would serve as our photographer, and spend a week in the Cloud Peak.

A week before I planned to meet up with Chris, my wife Bronwyn, son Rhys and several friends had stopped in Lander, Wyoming, to climb for a few days at Wild Iris, a sport climbing destination that Todd had developed in the 80s.

On our first day at Wild Iris, a small group of women assembled next to us. Unbeknownst to me, one of the women mentioned that they were climbing with Amy Skinner. I approached Amy hesitantly, and explained that I had been awarded the Live Your Dream Grant to put up a first ascent in honor of her late husband, not at all certain how this news would be received. First there was silence, and then a giant smile. She graciously introduced my wife and son to her daughters. She expressed how much it meant to her that the climbing community still remembered Todd and how he continued to inspire others in spirit. It was as though the Universe had drawn us all together to reaffirm that establishing a first ascent in honor of Todd and Paul, was not by accident.

Only a few days later, with smiles on their faces, and supportive hugs and kisses, Bronwyn and Rhys crawled in their rental car at the Rapid City airport and waved goodbye for the next seven days.

Our small trio arrived at the West Ten Sleep trailhead of the Cloud Peak Wilderness late in the afternoon with our packs stuffed to the gills. With the afternoon sun fading quickly we struck out to make camp by sunset. Every turn of the trail was magical. As we hiked along a meandering trout stream, with the wall hidden from view for the first 5 miles, my mind was a whirl with thoughts of loose rock, and hints of doubt.

Our small trio arrived at the West Ten Sleep trailhead of the Cloud Peak Wilderness late in the afternoon with our packs stuffed to the gills. With the afternoon sun fading quickly we struck out to make camp by sunset. Every turn of the trail was magical. As we hiked along a meandering trout stream, with the wall hidden from view for the first 5 miles, my mind was a whirl with thoughts of loose rock, and hints of doubt.

As we turned a corner, the Spider Web Wall came into view. Flanking the Wall, another large granite massif sat directly to its left creating a perfect cirque surrounding the Lost Twin Lakes. The idyllic setting was more impressive in person than all the photos Chris had shared with me prior to the trip.

We arrived in camp just before sunset to hundreds of hungry, but weak mosquitoes. The thin, cool mountain air helped thin the heard. Steve excavated a tent site and established our base camp. Chris grabbed his binoculars and began pointing out the intended line.

Staring up at our objective, thoughts of uncertainty returned, gnawing at me like a cancer. The wall was foreboding, and in the fading light my thoughts went in every directly like a snake that had been cornered. Fear of rockfall suddenly seemed unavoidable as Chris pointed out large flake systems that had cleaved off the wall since his last visit only a year ago. And then it dawned on me – we were the only ones in the entire cirque. If something went wrong, our only call for help was Steve. He would have to make the 4-5 hour hike back to the car and then drive another hour to make the emergency call. I tried the best I could to face my fear and talk through the plan for the day ahead.

The next morning we finalized our plan for Day 1. We would make a quick stop at Piana’s original gear stash, a small cave just below the formation. There, we would grab our bolting gear and approach the route from the left side of the Wall.

We hopped gigantic boulders as we hiked along the placid lake, as trout surfaced for an early morning snack of flies. Soon, we were standing on a grassy ledge overlooking the Twin Lakes and staring up at our objective.  We did some last minute gear sorting, and I took the first lead, which would deposit us about 200 feet above and just below the start of the climb.

We did some last minute gear sorting, and I took the first lead, which would deposit us about 200 feet above and just below the start of the climb.

Leading up an established route is a feeling that I am familiar with. But climbing without a topo and only an idea of where to go next is nearly paralyzing. For one thing, you don’t know if you are going to be able to protect the route as you climb above your last piece of gear, or have the luxury of clipping pre-placed bolts. There is no chalk to mark where someone else may have traveled, or anchors from which to gauge how far you have to climb before you reach the belay.

The climbing involves moving slowly, checking every hold to insure it’s not loose and double checking every gear placement. It is more like gardening, then climbing as I grabbed one loose rock, and then another, chucking them far enough off route to avoid hitting Chris and clearing a clean path for him to follow. When there is no gear to clip, and the risk of a fall, it is necessary to stop and put in a bolt.

We had agreed to place bolts only where necessary. If we had to drill a bolt, each was hand-drilled, taking a minimum of 20-25 minutes, while taking turns swinging the hammer. My only experience bolting prior to our trip had been using a luxurious Bosch (battery operated) drill and replacing bolts at a local sport crag, which took a total of a minute to sink the hole in the soft limestone. Chris was a pro when it came to bolting, and I had him laughing at my ineptitude at hand drilling.

As we moved up the wall making incremental progress, I became absorbed in puzzling our way up the wall. Thwarted by heading one direction, we reassessed and continued making upward progress. Chris was in his element, reading the rock like a skilled blackjack player counting cards. Even though Chris was well familiar with new routing, I was not and the amount of loose rock left me constantly on edge. If we weren’t tossing rock over our shoulders, one of us was excavating dirt and grass from the unclimbed cracks. As we moved up each pitch, the rock quality improved while the climbing difficulty increased. Near the end of our first day, we had established a high point over half way up the climb.

We drilled a bolt at our belay, rigged an anchor and descended to put in two more bolts before calling it a day. Steve was waiting for us at camp after a full day of shooting photos from various vantage points. We walked Steve through the first few pitches and Steve had already identified key features on the route, such as “the Gun pitch” resembling a pistol and other geographical features like “South America.”

It was surreal to see the route coming together piece by piece. As we previewed the pitches that still lie above our high point, I stared nervously at the wide chimney section that would more than likely be my lead the following day. I tried to remind myself I had climbed lots of chimneys, but not knowing the beta or what was in store was what worried me most.

The next morning we jumarred back to our high point. Tied in to the sharp end of the rope, I studied the obstacle in front of me – the gigantic loose flake that was listing and ready to fall into the void. I wanted to turn the lead over to Chris, but the thought of backing down was enough to propel me forward.

Chris suggested a thin seam out left. I set a piece, and then placed another while back cleaning the previous placement to avoid rope drag. Soon, I was twenty feet above the flake and below a small roof. Nothing mattered except what was directly in front of me. Soon, I was inside the chimney and moving with laser focus. Features appeared and I was able to get solid protection. “This pitch is awesome”, I yelled back down to Chris. I moved upward until I reached another overhang that required pulling on solid hand jams and then exited out left to a small ledge.

Chris left the belay and immediately dislodged the precarious flake, which instantly smashed into the ledge where he had previously stood before splintering into hundreds of pieces as it hit ledge after ledge. The smell of ozone filled the air. Chris swung through and tackled an unprotected off-width section that demanded his full attention.

From the off-width, Chris navigated up and left to a comfy bivy ledge. We put in a bolt, and studied the last bit of climbing that remained. One long pitch separated us from the summit. Chris racked up and set off following a series cracks and ledges before finding the summit blocks 180 feet above.

I followed slowly, retrieving the gear and marveling at Chris’ lead. I could see the summit ridge getting closer, and the uncertainty I had only days before, was quietly slipping away. The last few moves offered a reminder of the serious nature of new routing with loose rock littering the edge of the summit. I scrambled past Chris and found a safe spot to coil our ropes. The wide open expanse of the Cloud Peak Wilderness spilled out in front of us.

The reality of our ascent began to slowly filter in like the sunlight peaking through the lazy clouds drifting overhead. Surely, Todd and Paul had made this same hike off countless peaks hundreds of times.

The next morning, while looking back at the Spider Web Wall from our base camp, I spied the notorious “gun pitch” high up on the wall.

It reminded me of Todd and his cowboy persona, and the wild nature of the route. “What if we call it Wild Wild West?”, I suggested to Chris and Steve, who both nodded with approval.

Steve decided to head out early, but Chris and I remained on with two more days in the bank to explore more of what the Spider Web Wall offered. Chris pointed out another possible weakness just up and left from our new route. My hesitation was fading. We stuffed our packs full of gear and struck out for another day of new routing. Two pitches later, we were moving across the rockscape like astronaut explorers. Amazing cracks, wild climbing, and great protection unfolded before us. I looked back on the Lost Twin Lakes and saw the reflection of the granite walls that had become our new playground. I was living out my dream.