I recently took my friend Sam to the climbing gym for the first time. As we walked through the turnstile, his questions flowed like water. I tried to keep up by detailing climbing grades, styles of climbing, and the distinction between indoor and outdoor climbing. The wide screen in the corner was projecting a video of a climber moving fluidly over a sea of granite. Sam was mesmerized and demanded to know “where is that place?” “That’s Yosemite Valley”, I said with quiet reflection. At that moment, I knew Sam wanted to climb something that seemed impossible, and we understood one another completely.

Sixteen years earlier, and much like Sam, the gym was my playground. One evening, I grabbed a tattered climbing mag and thumbed through its pages. The feature article portrayed glossy images of Yosemite Valley, “the birthplace of American rock climbing”, and highlighted were the iconic routes up El Capitan and Half Dome. “Charlie, we have to go!”, I pleaded to my friend. Charlie smiled as if he was on to me. From that moment on, everything I did was a carefully calculated decision to one day climb the “Valley classics.”

Yosemite National Park, in California, is the crowned jewel of our national park system. Climbers travel to Yosemite from around the world to test themselves on the granite walls that were first pioneered by names like Robbins, Harding, Frost, and Chouinard. If you are a climber, Yosemite is synonymous with traditional big wall climbing.

With about a year of climbing under my belt, I was introduced to a local climber, Steve Wilger. Steve agreed to take me on my first trip to Yosemite. As the months turned into weeks, I climbed like a man possessed – crack climbing at Devil’s Tower, run out crystal climbing in the Needles of South Dakota, trips to Minnesota’s North Shore and more. I logged pitch after pitch, practiced aid climbing, jumarring, and readied myself for the big time – Yosemite!

We flew from Minnesota to San Francisco, rented a car and the next morning drove into Yosemite Valley. My jaw dropped, eyes popped out of my head, and stomach doubled over in knots. Still, I felt ready to see how I would measure up to the intimidating features that towered thousands of feet above us.

Soon, we were climbing. I tried to be smooth but was barely able to keep it together, due to the demanding style of climbing that Yosemite is known for. When Steve wasn’t leading us up a pitch, he followed me up each climb quietly, smiling and taking in the grandeur that was all around us. He climbed with confidence, and I envied his years of experience in the Valley.

That same trip, we had plans to climb the Regular Northwest Face of Half Dome as a multi-day route (big wall style). I had no big wall experience, and looking back on it now, probably no business attempting one. After what seemed like an endless debate, the decision was to tuck tail and return to the Valley. Half Dome would have to wait for another day.

Almost 13 years later, Steve and I returned with the singular objective to climb Half Dome in less than 24 hours, in a single push from ground to summit. I had matured as a climber, and even climbed the classic Nose route on El Capitan only a few years before. Steve wanted to summit Half Dome as badly as I did.

We launched for the summit. Six hours later were high off the ground and moving up the route like the mercury on a hot summer day. Pendulum traverses, changeovers, and wide chimneys awaited us, and we navigated each like clock-work. The day proved long, and near the top I was stopped abruptly by a difficult wide section. But, we overcame and topped out just shy of 24 hours with smiles as big as the Milky Way that glinted back at us with approval.

There is something about standing on the summit of a big mountain that only a climber can understand. It is not the summit that defines us, but rather the experience of getting there. Since that first trip to Yosemite, I have grown, not only as a human being, but as a climber who has perfected his craft. I took the skills that I learned at the small crags and boulders, and applied them in the alpine. It is a feeling of satisfaction as much as one of humility.

In this post, my friend and climbing partner Sevve Stember, reflects on his own progression as a climber through the lens of Yosemite National Park and highlights our summer ascent of three more climbs for Team 50×50, which we have dubbed “The High Sierra Trifecta.”

Home Again: A Better Version of my Former Self

By Contributing Author - Sevve Stember

It was 2006. I sat in the computer lab, staring blankly at the screen. A lack of direction seems to be a common pitfall among college students, and I was part of that statistic. To help quell the persistent feeling that I needed to do something more, I began applying to internships. “Ok, where’s the best possible place I could get an internship this summer?” I asked myself. Seconds later, I typed “Yosemite National Park internship” in to Google. Literally, the first hit was a PDF application for a Student Conservation Association internship.

Two weeks later, I got a call from a number I didn’t recognize. “Hi Sevve this is Vicky from Yosemite National Park. Do you have time to chat?” After that conversation and subsequent internship offer, my life would never be the same.  Driving through the naked expanse of the western United States was an exceptionally formative experience. I can still feel my world expanding with each mile that I drove.

Driving through the naked expanse of the western United States was an exceptionally formative experience. I can still feel my world expanding with each mile that I drove.

That summer, when I wasn’t chasing bears out of campgrounds (for real) or answering “What’s the best hike in the valley?” at the Visitor Center, I was out climbing. My eagerness to climb and to do so boldly was far greater than my skill set or sense of caution. That summer, I climbed 150+ pitches in around 10 weeks. My first 5.10 traditional line was sent. I escaped a few close calls, including a 50 foot whipper after getting off route on the Royal Arches, and walked away with nothing more than a little slab rash. At that point, it was the best summer of my life.

I returned back to Yosemite over the next two summer seasons. Despite living in Yosemite, there were always a few (many!) routes that evaded me. I think part of why I never climbed routes like “OZ” (Drug Dome, Tuolumne Meadows) was a nagging sense in the back of my mind that they might be too hard. And at the time, I think that was probably true.

After four years of being away, I returned back to Yosemite this past summer with my good friend Dan. Dan is working on a 50 x 50 project in which he plans to climb 50 inspiring climbs by his 50th birthday and I’ve been teaming up with him the last two summers to help him complete his project.

While I had been away from Yosemite, I had rounded myself out as a climber and improved at sport climbing and bouldering. I learned one of the most important lessons of my life: failing is the key to self-improvement and growth. In reality, I hadn’t trad climbed much since living in Yosemite Valley, except on a few occasions while on summer road trips. Nonetheless, returning to Yosemtie as a transformed climber and fresh eyes was more rewarding than I could’ve imagined. Routes that I had looked up at and dreamed of climbing for years were now becoming a reality.

My trip to to Yosemite started a little strange. I had posted a rideshare on Craigslist which resulted in sharing 20 hours of my life with a hippie named Charlie from England. He had recently been to the Rainbow Festival in the Uinta mountains of Utah. If you’ve never heard about it, suffice it to say it’s pretty out there. Highly entertaining stories were told. Stories of reading poetry while strolling around naked in a forest of lodgepole pine was only a sliver of what Charlie shared with us, while sitting around our campfire. Seriously, read up about it.

We arrived in Tuolumne Meadows by mid-afternoon, secured a campsite, and headed to Pot Hole Dome for some evening solos. Surrounded by Lembert Dome, Daff Dome, and Fairview Dome was like being at home again.

We arrived in Tuolumne Meadows by mid-afternoon, secured a campsite, and headed to Pot Hole Dome for some evening solos. Surrounded by Lembert Dome, Daff Dome, and Fairview Dome was like being at home again.

The next day Dan and I climbed a 5 pitch route on Mountaineers Dome called American Wet Daydream. The route was a good warmup for Dan and I to get our systems dialed, our lead head back on, and for me served as one of the few times I had placed trad gear in 2014. Things went well. The 4th and 5th pitches proved to be the most eventful, even though they weren’t the crux pitches. I lead pitch 4 which involved a traverse with no pro to a bolt, followed by placing really thin pro that was less than confidence inspiring. It was a good exercise in reducing risk as best you can and moving upwards. Dan calmly lead pitch 5 with thoughtful execution, which despite not getting an “R” rating (for being runout -no gear) had a 40 foot runout on 5.7 face climbing. Wooooeeee! We were back in the Sierra Nevada!

We had planned to hike into the Incredible Hulk in the nearby Sierra Nevada mountain range on the following day, but made a last minute change of plans. We would climb the most classic 5.10 in Tuolumne Meadows: OZ on Drug Dome (5 pitches, 5.10d). I had dreamed of climbing this route for years. The 2nd pitch is the crux and is essentially sport climbing 150 feet off the deck. Having spent most of my time the last 4 years sport climbing, this pitch went really well. It was funny to guess how I would’ve fared on it in 2008 or so. I also got to lead the money pitch- a 100+ foot dihedral with a hand crack splitting it. Climbing splitters in Indian Creek really helped me put this one together since it was just endless jams. I got to the top of this pitch with a smile from ear to ear. Dan brought us to the top through some interesting traverses and face climbing. Climb #2 went down smoothly!

Having spent most of my time the last 4 years sport climbing, this pitch went really well. It was funny to guess how I would’ve fared on it in 2008 or so. I also got to lead the money pitch- a 100+ foot dihedral with a hand crack splitting it. Climbing splitters in Indian Creek really helped me put this one together since it was just endless jams. I got to the top of this pitch with a smile from ear to ear. Dan brought us to the top through some interesting traverses and face climbing. Climb #2 went down smoothly!

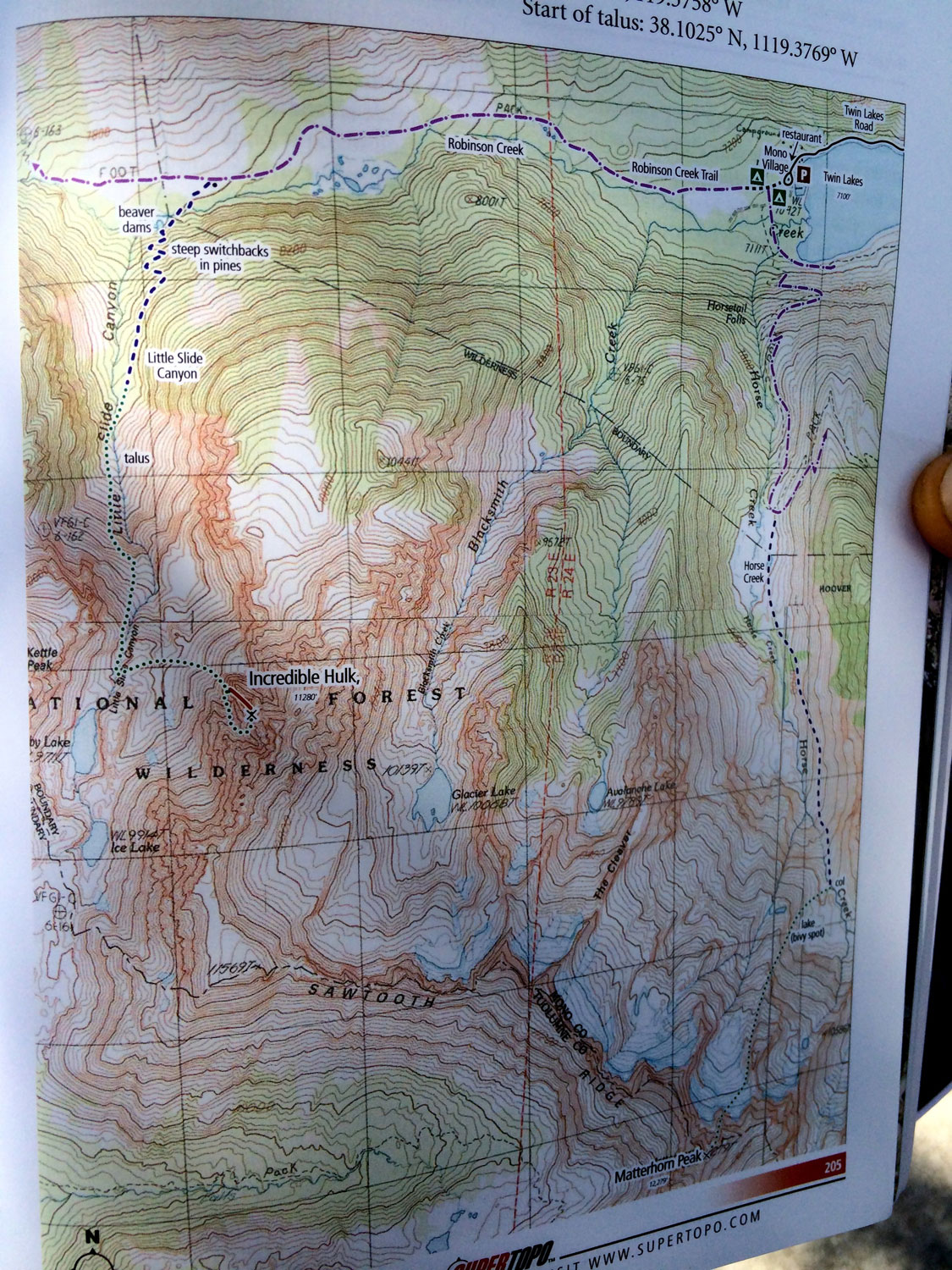

Alas, there was nothing left to do but get a permit at the Bridgeport Ranger Station, pack our sleeping and climbing gear, and hike five miles into one of the most highly regarded walls in the wilderness of the Sierra Nevada-The Incredible Hulk.

There was no hurry to get to our bivy spot, so we began our hike around midday. By the time we arrived at the talus field where we would stay for the night, there was an immaculate alpenglow on The Hulk.  Mind blown! To be clear, the feature is really intimidating. For me, climbing is a persistent flow between moments of radical self-confidence and profound self-doubt. Massive alpine objectives have a way of bringing questions to the forefront of your mind.

Mind blown! To be clear, the feature is really intimidating. For me, climbing is a persistent flow between moments of radical self-confidence and profound self-doubt. Massive alpine objectives have a way of bringing questions to the forefront of your mind.

The next morning we woke up at 4 a.m., poised to climb The Red Dihedral (5.10b, 1,500 feet, 12 pitches) . Neither of us slept well and my thermarest didn’t hold air. There was a party in front of us already. Ugh. Next, there was a party behind us that had only been climbing a year or so. They recently had a “whiskey fight” which Dan discovered when he asked why one of them had a black eye. Perfect.

I lead the rope stretching first pitch, passing the follower of the first party. Dan and I swapped leads on pitch 2 and 3, both having tricky gear placements. This brought us to the base of the beautiful crux pitch: a 130 foot dihedral with a splitter hand and finger crack. The party in front of us was taking repeated falls, ultimately resulting in the leader puking.

Dan handed over the crux pitch to me and I steadily made my way upwards. With just 20 feet left, I rested before the 10b crux moves, stemmed out really wide, and was soon on a small ledge helping the party in front of us rig a rappel so they could get down. Our friends behind us also decided they were in over their heads after taking a scary fall on the 5.9 pitch leading up to the dihedral.

The rest of the route felt really exposed for two reasons: first, there was nobody left on the route and second, there was some really aggressive looking weather systems on all sides of us. We gauged the direction the storms were moving as best as we could, but ultimately the safest way off The Hulk was up.

The upper half of the route was super fun. We were totally committed at that point; if bad weather rolled in we could only hunker down and wait it out. We had to summitt. This created a sense of urgency and a need to maximize efficiency. Each pitch went by in the type of flow that is often written about in climbing literature. We each led rope stretching pitches, getting to a belay stance with minimal gear left to build an anchor. Dan shouted down to me after leading pitch 9 “Let’s not weight the anchor ok?!”. I made sure not to.

Soon, we were squeezing between “the birth canal” (a tight squeeze chimney) which deposited us onto the summit. Looking out into the wild expanse, straddling Yosemite National Park and the Stanislaus National Forest, I had a deep sense of gratitude. I had first cut my teeth in the Sierra Nevada eight years before, not having the ability then that I had brought to The Hulk. In those eight years I had grown in so many ways and become a better version of my younger self. The one thing that had not changed, however, is the inspiration that I find in the wilderness. It was a memorable day, and one that will stick with me for years to come.

Looking out into the wild expanse, straddling Yosemite National Park and the Stanislaus National Forest, I had a deep sense of gratitude. I had first cut my teeth in the Sierra Nevada eight years before, not having the ability then that I had brought to The Hulk. In those eight years I had grown in so many ways and become a better version of my younger self. The one thing that had not changed, however, is the inspiration that I find in the wilderness. It was a memorable day, and one that will stick with me for years to come.

1 Comment

Brody

Good stuff Dan. I’m getting inspired to get back to the valley.